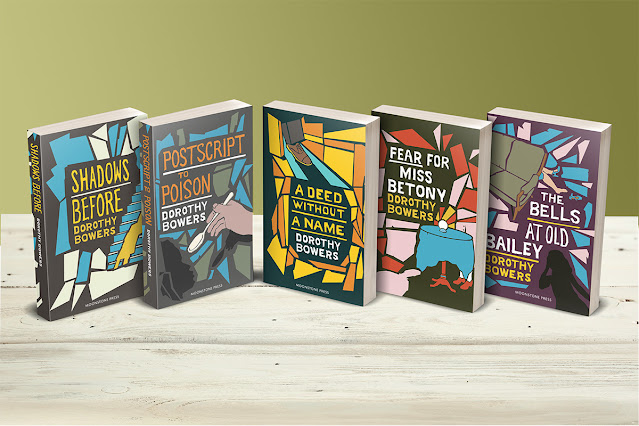

Last year my participation in Bodies From the Library revolved around Gladys Mitchell: this year it was Dorothy Bowers. If there’s one huge difference between the two, it is this: the Great Gladys wrote 66 crime books – Bowers wrote 5 and not much else, and the books are quite short.

Our revered captain at Bodies, John Curran, is a big fan of Dorothy Bowers – he says ‘Not only did Dorothy Bowers present her intelligent plots with meticulous attention to detail, but she did so with a genuine novelist’s eye and ear. Her 5 novels are gems of Golden Age detective fiction.’ – those who like her mention her dialogue and characters, and say she has an edge to her. it does seem she has been unjustly forgotten, probably because of her small output and early death.

She was born in 1902, and died of TB in 1948 after what Christopher Fowler in his Forgotten Authors series describes as a ‘not particularly joyful life’. On the plus side: she studied at Oxford University, published 5 books, and became a member of the Detection Club in 1948, the year she died, which implies she was highly-regarded by her fellow-writers. Martin Edwards quotes, in his book about the Detection Club, a letter in which she says how much it meant to her to be elected to the club.

So Bowers was 10 years younger than Dorothy L Sayers from whom she is not dissimilar, and 10 years older than Barbara Pym, novelist but not crime writer, and again many similarities.

She grew up in Monmouth in Wales, and seems to have lived with her parents for long stretches. Did she long to escape? There are a few letters in existence which suggest that very strongly.

She went to Oxford University – she wasn’t as some sources claim, one of the first women to ATTEND (that would come as a huge surprise to Dorothy L Sayers for example, and other women going back to 1870) - but it was only in 1920 that women were seen as full members of the university and were able to claim full degrees. She seems to have loved her time there and the friends she made (as was the case with her near-contemporaries – Sayers and Pym again). She graduated in 1926, and wrote to the college Principal: “I am going to miss Oxford strangely, in the manner one misses persons not places. I have loved it all, intensely, and those three years were the best in my life. I shall not forget your kindness in accepting me, for I know now how mediocre my work was, especially at that time.”

She took up teaching in various forms (classroom teacher, private tutor) – and every single reference to the profession in her books and letters would make you assume that she hated every moment of it. She talked at one point of having secretarial training as a way out. One gathers she would have liked a more exotic and adventurous life, but was constrained by money.

Again, similar to Sayers, but less success and perhaps a less happy life, a kind of antithesis of her. She never married and we just don’t know if she had any kind of romantic relationship. There’s a question that always arises these days – the only nuance we have is she was firm that she didn’t like to live in ‘monosexual’ organizations eg girls’ school, and there is no suggestion of any same-sex attraction.

In 1934 she was hoping to write a biography of Robert Sherard [name corrected, see comments below] – an odd character, notable mostly for his writings about and defence of Oscar Wilde. He’s a curiously sidelined figure to have picked (he sounds a most eccentric, temperamental and not particularly nice man from the sources available). He was still alive at this point and she corresponded with him, but nothing came of the project. If she had written it, you would imagine the book, and Sherard, would still both be forgotten now… There’s almost a wilfulness about her choices through her life, a determination not to do the useful or positive or best thing.

But any info is important, just because there is so little. There seems to be no extant photo of her: I asked her old Oxford college, St Anne’s, but they had none. Late on in my researches I thought I had found one on an Italian crime website and I got quite excited, but they seem to have simply lifted a photo from the death announcement of a completely different Dorothy Bowers of a similar era who died in Texas a while back. I was disappointed not only because I would like to see her, but also because the picture showed a rather glamorous smiling person, and I so hoped that was her… That picture is showing up on other sites now – and more since I first was looking - so I’m warning you to beware. I have put it with a cross on it so this is not used as more evidence.

For many years she composed crosswords for John O London’s Weekly, a very respectable literary magazine of the kind that was such a feature of life then, and also composed one for the alumni magazine of her Oxford college, and did them for another magazine.

She got to London during WW2, lived in Balham, and worked at the forerunner to the National Book League, and then at the BBC, and her book The Deed Without a Name seems to me to reflect an absolute love of London and London life. But it is very hard to track her during the war years, though we know that she was back in Monmouth by around 1945, and lived there or in the next county, Hereford, for the rest of her life – even though she inherited a reasonable sum of money when her father died in 1943 – enough, you’d have thought, to do and live anywhere she wanted. Perhaps her health was already deteriorating. She moved to Tupsley in Herefordshire after the war, and died there in 1948.

One last mystery about her life – in her will she left her house to one John Pigott, a bus conductor who lived at the same address as her. That’s all we know, though one internet source says that Pigott was after her death involved in a divorce case (unrelated to Bowers) – cited as co-respondent. Is it fanciful to hope that she may have had a joyful brief romance with this character? That he was a lothario of the transport system, flirtatious and charming, and brought some joy to her life?

I’ve mentioned and compared her to a lot of other writers here, all of them women. After re-reading the books and researching her for this talk, I am more than ever convinced that she should take her place proudly amongst those 20th century women writers who were often ignored or under-valued but wrote enthralling stories and helped to create a picture of life in that era.

There may be more entries to come on Dorothy Bowers and her books.

Thanks to the Random Genealogist, Matt Hall Random Genealogy (randomfh.blogspot.com). Thanks to Curtis Evans of the Passing Tramp blog, who has written about the scanty biographical details of Dorothy Bowers’ life. And also to Tom and Enid Shcantz of the Rue Morgue Press who wrote illuminating introduction when they republished the books in the early 2000s. And thanks to Martin Edwards, who has given me a little more information, so there may be another blogpost in future... .

"Roger Sherard"

ReplyDeleteer... do you mean Robert Sherard?

Yes I do, and I have now corrected it. thank you. I am guessing you are the only person who would ever have realized.... (no offence everyone else).

DeleteHis name was Robert Harborough Sherard, and I think my brain looked too quickly and combined the first two words.

Do you know anything interesting about him? - I had never heard of him before.

I came across this in some letters in a Cambridge University Archive. Not Sherard's own collection, which are elsewhere, but papers kept by a friend of his called Douglas Gray who lived in Australia.

I came across him years ago when I was doing some research on Oscar Wilde. Sherard probably wrote more books (usually the same book re-arranged) about Wilde than anyone else.

DeleteIn fact, as I got nowhere, could you or anyone else give assistance. When people talk of "the trials of Oscar Wilde" they usually mean the .action he took against the Marquess of Queensberry (actually the trial of the Marquess) and the trial when he was convicted of committing acts of gross indecency.

However, he was actually accused and prosecuted twice. In the first trial the jury could not agree on a verdict, so Wilde was re-tried.

True, the prosecutor and judge were changed at the second trial and evidence that had been excluded from the first trial was admitted, but the evidence of Wilde's guilt at the first trial was powerful. Obviously at least one juror at the first trial refused to convict on on what was still pretty convincing evidence. I wondered how often this happened, both with sexual offences and generally. There was an old joke about a judge saying to an acquitted defendant "You have been found not guilty by a Snaresbrook jury and may leave the court with no other stain on your character."

It wasn't until 1967 that majority verdicts were allowed, but I wondered how long a history there had been of refusals to convict before that. For obvious reasons - the secrecy of jurors' decisions, most obviously - it would be difficult to learn, but as far as I know, no research at all was done into the matter before the law was changed, despite vague allegations of "nobbled" jurors.

What an interesting question, and definitely one that it would be good to know about. I have no idea.

DeleteOf course that was the setup in Sayers Strong Poison - one juror stood out against finding Harriet Vane guilty, a retrial was ordered, and that gave Wimsey a short time to find new evidence. That's as far as my knowledge extends.

There've been cases recently - most notably Clive Ponting - where juries have rejected cases brought on "security" grounds, but there must be a hidden history. In the 17th century there were cases of judges punishing juries that returned "wrong" verdicts and in the late 18th and early 19th centuries petty thieves who faced death sentences are said to have been acquitted, regardless of evidence.

DeleteVictimless crimes like homosexual acts are probably one area where people might have felt entitled to reject the actual law, even if others thought they were offences against god, deserving worse punishment.

In Liverpool there was a legend of a defence lawyer saying 'you surely cannot convict my client on the unsupported evidence of 12 Liverpool policemen', and while that may be mythical, there was a cheery anti-police and anti-establishment feel there that might make it harder to get a conviction. And very recently in Bristol the protesters who toppled the Colston statue were acquitted in a fairly blatant case.

DeleteBut as you say there is probably a long hidden history, and it would be fascinating to know more, but difficult to know where to start.

I always like finding out more about authors who aren't very well known, Moira. I find it interesting to learn what drew them to writing and what sort of lives they led. You make an interesting point, too, about the limited number of books she wrote. Some people really are a lot more prolific than others, and I've found that Martin Edwards is right: there are some real gems among those authors whose work didn't find a huge audience, at least at first.

ReplyDeleteIt is so interesting, Margot. And there were so many authors, there is always someone new to discover from that era.

DeleteI don’t know how to reach you but I have a photo of Dorothy. My mother was evacuated to Monmouth and spent time with her. I have a photograph from 1941 with them stood in front of Dorothy’s House. I’d love to ask you about the house . . . Please message me at gavind2@hotmail.co.uk.

ReplyDeleteGreat to hear from you, I have emailed you

Delete