To mark the 100th anniversary of the end of the First Word War, my daughter Barbara Speed and I are doing a joint post – here on my blog and on her poetry newsletter, Lunch Poem. (Details at the end of the post)

I saw a man this morning

(sometimes known as Achilles in the Trench)

by Patrick Shaw-Stewart

written around 1915

I saw a man this morning

Who did not wish to die

I ask, and cannot answer,

If otherwise wish I.

Fair broke the day this morning

Against the Dardanelles;

The breeze blew soft, the morn's cheeks

Were cold as cold sea-shells.

But other shells are waiting

Across the Aegean sea,

Shrapnel and high explosive,

Shells and hells for me.

O hell of ships and cities,

Hell of men like me,

Fatal second Helen,

Why must I follow thee?

Achilles came to Troyland

And I to Chersonese:

He turned from wrath to battle,

And I from three days' peace.

Was it so hard, Achilles,

So very hard to die?

Thou knewest and I know not—

So much the happier I.

I will go back this morning

From Imbros over the sea;

Stand in the trench, Achilles,

Flame-capped, and shout for me.

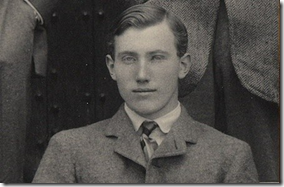

commentary: Patrick Shaw-Stewart died in the First World War in 1917 at the age of 29. He stands for all the classically-educated young men, public school officers, who must have thought war would be much more like Homer and less like Gallipoli.

He was a brilliant scholar - educated at Eton and then Balliol College Oxford - and spoke Ancient Greek to the locals when deployed in Greece. He was present at Rupert Brooke’s funeral. This poem was found after his death, written on the endpapers of his copy of AE Housman’s A Shropshire Lad. (You couldn’t make it up).

George Orwell (in a piece about Rudyard Kipling) writes persuasively about a point at which the world changed: by 1942 there could be no belief that having right on your side was enough in a battle, and so being part of the forces for good did not give you an edge over your enemy. Talking of the ‘post-Hitler mind’, Orwell says:

No-one, in our time, believes in any sanction greater than military power; no-one believes it is possible to overcome force except by greater force.

Patrick Shaw-Stewart was surely part of the earlier generation, still with the belief that, at the very least, the gods punish hubris. The classical references in his poem are carefully worked out, and the question he asks – well isn’t it obvious what the answer would be to modern eyes? Of course he should not want to die, even in a good cause.

The final lines of this poem refer to Achilles’s response to the death of Patroclus:

Stand in the trench, Achilles,

Flame-capped, and shout for me

For me this couplet is one of the abiding images of the First World War, one of the saddest and most memorable. When I first read the poem, many many years ago, I thought he was asking Achilles for encouragement, asking to be cheered on. But he is not. In Homer’s Iliad (Book 18), Achilles’ great love, Patroclus, has been killed by the Trojans. Achilles is devastated (this is my own translation from the Ancient Greek):

Fire wreathed round Achilles’ head, like that round burning ships, rising up towards Heaven. He came from the wall to the trench, and stood there and shouted: he cried aloud like a war trumpet, and the Trojans were dumbfounded and thunderstruck. The flames capped his head, and three times he roared and shouted, and three times the Trojans fell back in chaos, overwhelmed.

Patrick Shaw-Stewart is asking for someone to mourn him, someone to care passionately if he dies.

A hundred years later that is the least, and the most, that we can do for him and for all the other lost dreams, and futures, and lives of the First World War.

------------------

The top picture is The Resurrection of the Soldiers by Stanley Spencer.

I recently read a most wonderful novel about the First World War, and the toll it took particularly on the young, and strongly recommend it. It is The Skylark War, by my friend Hilary McKay.

--------------------------

Subscribers to the newsletter are sent a poem every couple of weeks, along with a commentary on it. Just right - not too demanding and a delight to be sent something beautiful, usually at lunchtime. You can sign up for the newsletter here .

What a powerful post (and poem), Moira. I couldn't agree more about the importance of remembering those who died, and giving some thought to those who had to go on without them.

ReplyDeleteThanks Margot. A day for us all to take time out and think about history.

DeleteThat is a lovely poem and very moving. When I think of Veteran's Day I always think of my father and World War II and am glad to be reminded that there was a generation before them that suffered so much from World War I.

ReplyDeleteThanks Tracy, and my respects to your family. There can be no family untouched.

DeleteAs Sharon and I were on our way to Regina today for a football game we listened to Remembrance Day stories and national service. Until this morning I had not heard of the sinking of the Canadian hospital ship, Llandovery Castle, by a German submarine in WW I. Among those lost were 14 Canadian nurses.

ReplyDeleteSergeant Arthur Knight on the lifeboat with them after the sinking said:

"Unflinchingly and calmly, as steady and collected as if on parade, without a complaint or a single sign of emotion, our fourteen devoted nursing sisters faced the terrible ordeal of certain death--only a matter of minutes--as our lifeboat neared that mad whirlpool of waters where all human power was helpless."

He went under and came up in the water 3 times after the lifeboat capsized. He was the only survivor from the lifeboat.

Oh my goodness what an extraordinary story Bill. It is almost unimaginable.

DeleteMoira, thanks for sharing Patrick Shaw-Stewart's affecting poem as well as your excellent interpretation that made it easier for me to understand it. I liked Stewart's poetic style because I haven't read many such styles. But what a period he lived in, and died so young. Unimaginably sad, really.

ReplyDeleteIsn't it just Prashant - all those young men. It is hard to contemplate.

DeleteThis is so touching, Moira. My great uncle Richard died in 1916 at Passchendaele and his body was never identified. He was twenty-six. A few years ago we went to find his name on the memorial at Tyne Cot. He came from a modest working class family and I am sure I was the first member of the family to go. At any rate he has not been forgotten.

ReplyDeleteThat is both sad and heart-warming, Chrissie, thanks for telling us. Oh those young men...

DeleteSo moving, Moira. I was doing research on my great-grandfather (killed 1916) and came across a Sargent portrait of a young officer and poet, E W Tennant. The portrait is somehow so tender and very moving. https://twitter.com/saraoleary/status/1061380421550772224

ReplyDeleteWhat a beautiful picture - thanks Sara. Sometimes people associate Sargent just with society portraits, but he did so much more than that.

DeletePerhaps Sargent's largest painting - and not a portrait - came out of WWI: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/23722

DeleteExtraordinary, yes. Thanks for providing the link.

DeleteVery apt. Incredibly sad.

ReplyDeleteIndeed, a sad remembrance for all of us.

Delete