This is the end of the special Christmas entries on the blog. I wondered about doing – as I have in the past – a post about going back to work once the festivities are done: but will just link to this Bridget Jones entry, as her description has, in my view, never been bettered. And instead, here’s an overview of a mediaeval Christmas, and wedding, from one of the great sweeping true history romances of all time. Just to cheer you all up.

Katherine by Anya Seton

published 1954

It snowed softly in Leicester on Christmas Day of the year 1380, and to the hundreds of guests sheltered at the castle and the Abbey of St. Mary-in-the-Meadows, and in other foundations and lodgings throughout the town, the pure white drifts were good omen for young Henry of Bolingbroke’s wedding to little Mary de Bohun. Of all the Duke’s country castles since he had abandoned Bolingbroke, Kenilworth and Leicester were his favourites, and the latter was the more fitting for the marriage of the Lancastrian heir.

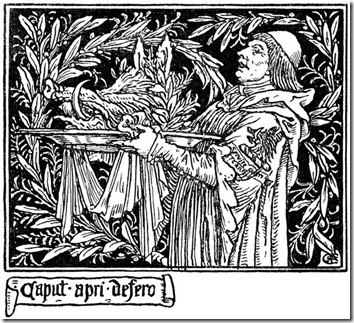

This joint celebration of Christmastide and a wedding had tuned Leicester to feverish pitch. Each night mummers came to the castle dressed as bears and devils and green men, to scamper on their hobby-horses through the Great Hall. And each night a fresh boar’s head was borne in to the feasting and greeted by its own carol, “Caput Apri Defero.”

And this Christmastide was a feast of light and music. Scented yule candles burned all night, while the streets of Leicester were extravagantly lit by torches that cast their rosy flames on the snow. The waits sang “Here We Come a-Wassailing” in the courtyards, the monks chanted “Veni Emmanuel” in the churches, and in the castle gallery the Duke’s minstrels played carols without ceasing.

On the night of the wedding there was a riotous banquet in the castle hall. Katherine’s sides ached from laughing at the Lord of Misrule, who was dressed in a fool’s costume, a-jingle with tiny bells, and wore a tinsel crown on his head to show that he was king and must be obeyed. The Lord of Misrule… won laughter even from the frightened little bride when he seized a peacock feather in lieu of sword and solemnly knighted Jupiter, the Duke’s oldest hound.

commentary: Last year I described how I (and some other women of my generation) loved Katherine as a piece of romantic historical fiction – and how it lives on despite its 1950s trappings, because of the extraordinary true story it tells. (And last week we had another entry on the Susan Howatch masterpiece based on the same history: Wheel of Fortune.)

This description of Christmas is very typical of the book: written in that slightly annoying cod-mediaeval way, but actually summoning up an attractive picture of a community enjoying the feast: Life may not have been that great the rest of the time, so the feasts and celebrations were particularly important.

The boar’s head at the feast is an authentic period detail. Andrew Gant, in his marvellous book on Christmas Carols, says this:

The boar’s head feast, with its music, runs through accounts of large-scale Christmas festivities from the earliest days….Midwinter feasting, naturally enough, has always helped stave off the long British winter. Bones found at Stonehenge and elsewhere suggest large gatherings munching on pig and other delicacies. Later, romantically-minded scholar poets tried hard to link the boar’s head festivals with various religious practices of the Vikings. One of the first, much-quoted accounts is of the occasion in June 1170 when Henry II appointed his young son to rule jointly with him. Holinshed (writing much later, of course) says ‘king Henrie the father serued his sonne at the table as sewer, bringing vp the boars head with trumpets before it, according to the maner’, implying a well-established ceremonial to go with the entry of the dish, complete with music.Gant says that while the music goes back a long way, the Boar’s Head Carol as mentioned above first appeared in 1521. But that’s a tiny detail. It is more important that this is a book that has given endless pleasure to me and many others.

And the boar’s head tradition continued into the 20th century, as I found out reading a biography of Queen Mary – in literary terms, that’s the May of Teck for whom the hostel in The Girls of Slender Means was named. One of her German relations, the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, would send three freshly-killed boars’ heads over to England each Christmas, including one for the mainstream Royal family at Sandringham.

One of the Boar’s Head pictures was a British Christmas stamp in 1978. Another is a Christmas illustration by Walter Crane from 1895.

I got exactly the same feeling, Moira, in reading your post: that description of the celebrations is really joyful when you consider the conditions most people lived in at that time. You can just feel people wanting to enjoy themselves. And thanks for sharing the background on the boar's head. Trust you to do some fascinating research on that and teach us.

ReplyDeleteOh thanks for those kind words Margot! One of the things I most love is when I can link things up via my reading, and it's so nice when someone appreciates that.

DeleteLooking back at your posts on Howatch's book, I think I would prefer that one, but both are covering an interesting subject that I would enjoy reading about.

ReplyDeleteI wonder if Seton's Katherine is one that it's best to first read when young? Like Catcher in the Rye maybe? Wheel of Fortune is fabulous, if very long. I want to read it again now.

Delete