published in English 2012, translation by Ann Goldstein

book 1 of the Neapolitan Series

[Elena goes on holiday to Ischia]

In the beginning, after all the fears that my mother had inoculated me with and all the troubles I had with my body, I spent the time on the terrace, dressed, writing a letter to Lila every day, each one filled with questions, clever remarks, lively descriptions of the island. But one morning Nella made fun of me, saying, “What are you doing like this? Put on your bathing suit.” When I put it on she burst out laughing, she thought it was old-fashioned. She sewed me one that she said was more modern, very low over the bosom, more fitted around the bottom, of a beautiful blue. I tried it on and she was enthusiastic, she said it was time I went to the sea, enough of the terrace…

[A year later, Lina has a job looking after some children]

Sea, sun, and money. I was to go every day to a place that I knew nothing about, it had a foreign name: Sea Garden…

Every morning I crossed the city with the three little girls, on the crowded buses, and took them to that bright-coloured place of beach umbrellas, blue sea, concrete platforms, students, well-off women a lot of free time, showy women, with greedy faces. I was polite to the attendants who tried to start conversations. I looked after the children, taking them for long swims, and showing off the bathing suit that Nella had made for me the year before.

observations: Elena Ferrante has a very particular place in the contemporary literary canon: she’s an Italian novelist who shuns publicity and seems to be close to crossing from cult status to bestsellerdom in the USA and the UK, while apparently less popular in her home country of Italy. The whole scenario is covered in this Guardian article last year, and another one this weekend.

I liked reading this book, but am also looking forward to the subsequent books, which I anticipate enjoying even more: the series tells the story of a friendship between two women, and here they are children and teenagers. In any such bildungsroman I am always waiting impatiently for the young years to be done – even though the point is usually the lasting effect of those years on the future personalities. Shoes play an important part in this book, but I am guessing we haven’t heard the last of them, so I will probably feature them in a future entry – I am pretty much convinced I will be reading the whole quartet.

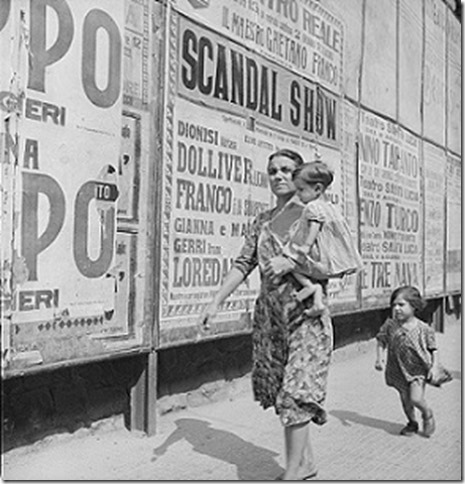

The picture of Naples life in the late 1940s and 50s is fascinating and convincing: it’s like watching a Fellini film or seeing black and white photos such as the ones with this entry. The limitations of the girls’ lives are spelt out – they come from working families, but there is little money and they almost never leave their own neighbourhood. The men have control, and there is a lot of violence. There are characters with underworld connections. One of the young women is lucky enough to get a few years’ more education, but most of the young people (male and female) have no such expectation. Their lives are bounded and predictable, and the men are full of ideas of honour and shame, and are violent and tiresome in pursuit of that.

There is a marvellous extended description of the runup to a wedding, and then the event itself, with its community feel, its many important choices and decisions, and the outrage of guests who don’t feel they got the proper treatment. The affianced couple – going up in the world – displayed ‘kindness and politeness toward everyone, as if they were John and Jacqueline Kennedy visiting a neighbourhood of indigents.’

Many references to the English-language versions of the books mention the wonderful translation. I wish I spoke Italian, so I could judge this better. The translator is an editor at the New Yorker, which pretty much inures her from any criticism in US intellectual circles. I find the language used quite clumsy, but perhaps this is just reflecting the original? For example, the first couple of sentences of the first extract above are rather odd, particularly ‘What are you doing like this?’

But this is just my interest. I am very keen to move on and read the next in the series.

The photographs are as follows:

"Young women of Naples in swimsuit, Italy 1948" by Anonymous - Old photo. Licenced under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

"Children of Naples, Italy" by Wayne Miller, Photographer (NARA record: 2083745) - U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Licenced under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

"People on beach - Naples, Italy - April 21 1945" by Anonymous - Old photo. Licenced under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Any horse heads? No? Probably not for me, cheers

ReplyDeleteActually there is an underworld connection - I was a bit slow, but there's a man who runs the neighbourhood, and whom everyone needs to be cautious about, and I think we're meant to assume he's running the local camorra.... so you see...

DeleteI wondered about that sentence too, Moira. There were a few other places, too, where I noticed the writing and wondered if it was a translation issue. The characters don't sound particularly happy - makes it seem rather a moody book. But the look at life in that part of Italy at that time sounds interesting. Glad you liked it enough to read more in the series.

ReplyDeleteI think it's a really good book, and it does override whatever small issues I had with it. And you really want to know what's going to happen to these characters.

DeleteThanks. Moira. I was wondering about this after reading that Guardian article and you've made me want to read it. Might be good for my (very cosmopolitan) book group. And how refreshing that the author can get away with shunning publicity.

ReplyDeleteYes - the story of her refusal to engage is fascinating, isn't it? And I think it's going to be popular with a lot of women's bookgroups. It's quite demanding to begin with, wouldn't suit everyone, but if you stick with it the rewards are high, and I suspect will be even higher in the later books.

DeleteNot read this one Moira - in that example you site, "What are you doing like this?" I can gues quite easily what it was in Italian, with the this ("cosi") emphasised to partly make up for the implicit 'dressed' in front of it (sheer conjecture - probably all wrong). I'll have to get it now Moira - I'm off back home on Thursday so will see if I can find a copy at my local libreria.

ReplyDeleteOh thanks Sergio that's interesting - now what I really need is for you to read it in Italian AND English so you can give me a verdict on the translation. It is a very interesting book...

DeleteMoira, about translated works (not that I have read many), I often wonder how close they are to the original. To the best of my knowledge, translations are by and large faithful to the original, as evident from the passage you have quoted, I think. Tell it like it is, so to speak.

ReplyDeleteIt's a really interesting issue, isn't it Prashant? Translations can vary a lot - I'm sure most of them are very good, but you can't always be sure. I wish I spoke more languages!

DeleteThis sounds very interesting. I will put it on a list for consideration. And wait and see how the books develop.

ReplyDeleteI'm hoping to read the rest of them Tracy, so you can take an observer role for now....

Delete