The Constant Nymph by Margaret Kennedy

published 1924

I am obsessed with the idea of Margaret Kennedy’s phenomenal best-selling book, and its place in popular culture.

There is a post on the book itself here, and a list of all the posts it is mentioned in.

I have mentioned my fascination before – in (of all things) my take on Pamela Brown’s Golden Pavements, a forgotten but splendid YA book about drama students. One of the young actresses gets the role of Tessa in a play of the book, and I used that as an excuse to list some other notable mentions of Constant Nymph in other books, from Dorothy L Sayers via Nancy Mitford and onwards to Antonia Forest.

In a post on another Kennedy book, Lucy Carmichael, I described the earlier book like this

The luscious Constant Nymph is a terrific melodrama with a rather uncomfortable plot involving an over-young woman and an older relation-by-marriage. Kennedy tilts the authorial scales so you can convince yourself that this – including breaking up a marriage – is all perfectly fine (the abandoned wife is treated most ruthlessly), although also tragically sad. It has been beloved by teenage girls and many others since it was first published in 1924, when it was a massive and rather risque bestseller.

But what has always fascinated me is its unique high/low culture position: everyone loved it, not just teenage girls. The list of famous and intellectual people who admired it is remarkable: AE Housman, Thomas Hardy, Arnold Bennett, JM Barrie, Cyril Connolly, Karen Blixen. (Anita Brookner – see below- thinks it may be more of a men’s book than appealing to women, which at first glance looks unlikely, but becomes strangely convincing.)

Since those early posts, the much-loved Backlisted podcast has done an episode using Constant Nymph as a starting point – I am happy to say that this blog is featured therein.

And I’ve collected a few more mentions: during WWII Jean-Paul Sartre asked Simone de Beauvoir to send him a new Kennedy book, Solitude en Commun. (I think I have safely matched this – though it wasn’t trivial – to the 1936 novel Together and Apart). Once he has it, he says ‘it recalls some of the charm of the Constant Nymph. Not all the charm: the subject is less appealing – but still and all I was completely charmed this morning at the restaurant as I read it.’

In an Ethel Lina White crime novel, The First Time He Died, a schoolgirl who has just discovered she has a crush on someone is described like this:

The girl went home feeling that every cell in her body had been subjected to a chemical change. For the first time she experienced the chaotic upheaval of Nature. Hitherto she had been a boy, and would have been murderous to a Constant Nymph on the hockey field.

I recently blogged on the books of Annabel Davis-Goff – in The Dower House young Molly, going to stay with her cousin for a dance, is ‘carrying a small suitcase containing her nightdress, a shabby teddy bear, and The Constant Nymph.’

There is nothing you can say about this book that hasn’t been said before – but it continues to fascinate and to enchant and seem to call out to be analysed yet again. Anita Brookner wrote a most perceptive introduction to the Virago edition in the 1980s, and she lists the ‘three tremendous forces which give the novel its power: the mercilessness of the privileged, the subversive appeal of the wrecker, and the fatality of the wound inflicted by passion.’

A more recent introduction, by Joanna Briscoe in 2014, says ‘the years have not been kind to The Constant Nymph… slipping from public awareness as its author has fallen perilously out of fashion’.

I have frequently mentioned the Claud Cockburn book Bestseller, about the popular books of the first half of the 20th century: he is particularly good on Constant Nymph.

It is an extraordinary book, and I would love to hear whether new generations continue to discover it… It is still in print.

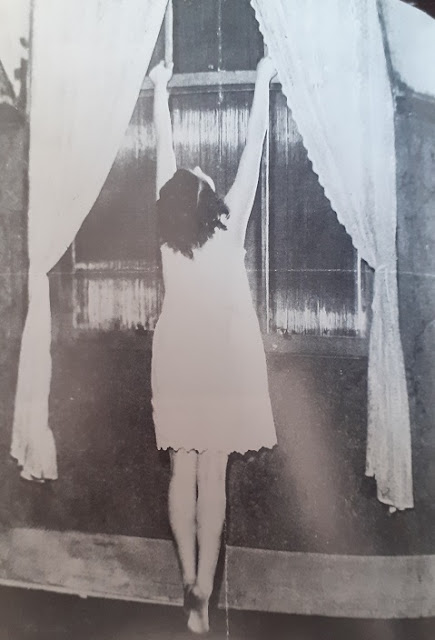

There have been numerous adaptations – the striking picture shows Edna Best playing Tessa in a West End play of the book in 1926. She was starring alongside first Noel Coward and then John Gielgud.

Most pictures of Margaret Kennedy do not seem flattering. This one is from the Smithsonian Institute.

I was brought back to Nymph after being recommended another book by Kennedy, which sent me reading more – another post will follow…

It's fascinating, isn't it, Moira, when a book captures the imagination, as that one did, so that everyone seems to know it and talk about it. It's been mentioned a lot, as you show us, and it makes me wonder what the elements are of a novel that has that much influence. Just as interesting, there are books (and I'm sure you know a lot of them) that completely fade from attention, even though their quality is equal to or greater than those iconic books...

ReplyDeleteI know - it is so difficult to predict, or to work out in the past, what makes one book a bestseller and another a not, one book lives for ever and another is forgotten. Fascinating topic!

DeleteWhat an interesting post. It's years since I read The Constant Nymph and you make me want to read it again.

ReplyDeleteGolden Pavements is my favourite of the Blue Door books, probably because I owned it as a child and read it a lot.

I'll be interested to hear what you make of it if you do re-read. And so nice that you love Golden Pavements - I always loved Swish of the Curtain so much, but Golden Pavements is a strong competitor because of that wonderful picture of young people in London at that time.

DeleteI came across the Constant Nymph in a holiday cottage a few years ago, and read it because of the Ginty Marlow connection. I found it both extraordinary and appalling in equal measure. In an early scene the teenage girls strip off and swim in the lake in front of Lewis Dodds. I know attitudes to children being naked have changed over the last century - but girls that age? One of them is shortly to be married. And later in the book, Lewis is clearly grooming Tessa, trying to make her stay the way he likes her, even undoing her plaits at one point because he likes her hair loose. The main reason he seems to be attracted to Tessa is that she knows that he is a selfish bastard but accepts him that way and won't try to change him. In fact, the more I think about this book, the more angry I get, but I suppose it is a useful illustration of what attitudes to women / relationships were like in the past. I also find it interesting that Antonia Forest used Lewis Dodd's name for two of her 'villains' - Lewis Foley and Edwin Dodd.

ReplyDeleteIt is exactly the book to find in a holiday cottage, I would say. And yes it makes for uncomfortable reading at times. But still some of us get some magic from it - not you? Each time I read it I get more horrified by Lewis Dodds, a monster of selfishness.

DeleteGreat catch on Forest naming....

I don't know about magic, but I did appreciate how well written it was and felt very involved while I was reading it. Perhaps if I'd read it as an impressionable teenager I'd have fallen for it more. I'd certainly never want to reread it - such a bleak ending for all the characters.

DeleteI think I was truly surprised when I read it the first time that it had such an ending, I wasn't expecting it...

Delete