published 1953, set 1900

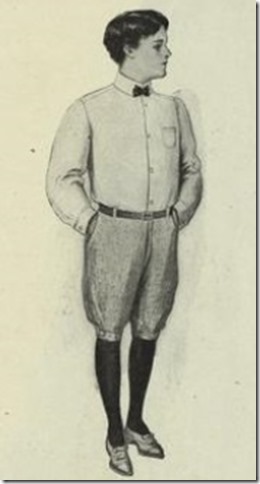

How could I not get hot? I looked at Marcus. He was wearing a light flannel suit. His shirt was not open but it was loose at the neck; his knickers could not be called shorts, for they came well below his knees but they also were loose, they flapped, they let the air in. Below them, not quite meeting them, he wore a pair of thin grey stockings neatly turned over their supporting garters; and on his feet – wonder of wonders – not boots but what then were called low shoes. To a lightly clad child of today this would seem thick winter wear; to me it might have been a bathing-suit, it looked so inadequate to the proper, serious function of clothes.

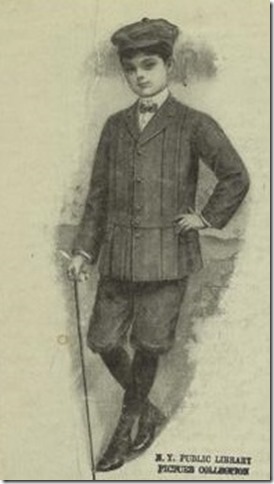

I [was] wearing an Eton collar and a bow tie; a Norfolk jacket cut very high across the chest,

incised leather buttons, round as bullets, conscientiously done up, and a belt which I have drawn more tightly than I need have. My breeches were secured below the knee with a cloth strap and buckle, but these were hidden by thick black stockings, the garters of which, coming just below the straps, put a double strain on the circulation of my legs. To complete the picture, a pair of obviously new boots, looking larger for being new, and with the tabs, which I must have forgotten to tuck in, standing up boldly.

incised leather buttons, round as bullets, conscientiously done up, and a belt which I have drawn more tightly than I need have. My breeches were secured below the knee with a cloth strap and buckle, but these were hidden by thick black stockings, the garters of which, coming just below the straps, put a double strain on the circulation of my legs. To complete the picture, a pair of obviously new boots, looking larger for being new, and with the tabs, which I must have forgotten to tuck in, standing up boldly.observations: The first line of The Go Between – The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there – is one of the most famous, and it’s a stock question in literary quizzes. The book was made into an iconic film in 1971, and its place in the culture is assured. Last night a new adaptation of it was shown on BBC TV.

I picked it up recently, having always assumed I’d read it – I felt I knew everything about it, and I had seen the film, and I knew it was about a bad incident in a young boy’s life, one that stunted his emotions. I was looking at books about long, hot and disastrous summers for a potential article. The Go Between is an archetype of such books, so I thought I’d remind myself. But I quickly realized I had never read it – because it was so good, I would have remembered it. It is a 5-star book, and I was astounded by it: it was so involving, so clever, so unexpected – even though I knew the plot. Hartley was a monstrously clever writer, the book has an amazing structure and an amazing voice, and is a wonderful picture of a young boy - in a time and place that are, as he says, a foreign country, but one that he makes so real. You feel you know young Leo very well indeed, as he scampers around a country estate on a visit to a schoolfriend in July 1900.

His clothes are a big deal – he hasn’t brought summer things with him on his visit, so when the temperature rises he suffers in his thick Norfolk jacket. Lovely Marion, his host’s sister, helps him out by getting him a lighter suit. His friend, Marcus, is hilariously awful with his serious comments on how Leo must behave and dress – don’t wear your cricket cap, don’t pick up your clothes (leave them for the servants), don’t wear a ready-made tie, don’t be a cad.

Leo is pulled into carrying messages between Marion and a local farmer (way below her in class terms). There is a heat wave – every day Leo goes to check the maximum temperature, hoping it might reach 100F. But it doesn’t, symbolic of all the disappointments he is going to suffer. There is a cricket match and a supper and concert.

There are endless guests, an ongoing houseparty, and there is going to be a ball. Is there going to be an engagement too? Leo, surprisingly, dabbles in a little magic and is obsessed with horoscopes. Nothing is going to end well.

It is a very sad book, very melancholy. But I love the epilogue which was satisfying and perfect.

I made endless notes of phrases and sentences and ideas that I liked. From the beginning – the older Leo, in his 60s, says ‘It was 11.5, five minutes later than my habitual bedtime. I felt guilty at being still up…’ so you know all about him just from that.

The older Leo imagines speaking to his younger self, with these words that should sound ludicrous but instead are heart-breaking:

‘Well, it was you who let me down, and I will tell you how. You flew too near to the sun, and you were scorched. This cindery creature is what you made me.’And later: ‘I haven’t much life left to spoil’. And again: ‘I had not been so long at school that I had lost the power of crying.’

There is much clever play with Marion’s more suitable lover – his name is Hugh and there is a repeated Hugh/you/who? motif. (Strangely a very modern novel I read recently, by Marina Endicott, has the same trope – it’s actually called Close to Hugh.)

The pictures are from advertisements at the NYPL. Leo and Marcus must have been just too old for sailor suits – he never mentions them, but they feature a lot on young boys in photos, illustrations and adverts of the era.

LP Hartley’s novella Simonetta Perkins featured on the blog on Valentine’s Day.

I watched this last night, started with half-an-eye and was quickly hooked which is unusual - I haven't read the book, although of course I know the plot but your comments really make me want to - that's two classics I've added to my list this morning!

ReplyDeleteHonestly - such a good book! I wish someone had told me to read it in former times...

DeleteI loved this book and found the movie, the early one, a bit disappointing, haven't seen the latest version.

ReplyDeleteI don't think anything quite matches up to the book....

DeleteI do love that very famous opening line, Moira! And what a clever plot idea, too. I think, though, that it's really the writing style that draws one in. Saying so much with relatively so few words takes quite a deft hand. And, all that aside, isn't it a great to discover a book that's a real treat? Especially one you thought you'd already read?

ReplyDeleteYes, he was a great stylist and a very talented writer. And yes, what an unexpected joy to discover something so late...

DeleteReally like this book a lot and also think the first movie version id very impressive. Must admit though, could;t quite get the energy to see the new TV version - was it any good?

ReplyDeleteI have recorded it but not watched it yet - have heard mixed reactions from others.

DeleteI somehow couldn't face watching the TV version on Sunday. I read the book and saw the film long ago and they have stayed vividly in my mind. They've meshed together so perfectly in my memory that I didn't want to add anything to them.

ReplyDeleteI know exactly what you mean Chrissie. I just wish someone had told me ages ago to read the book!

DeleteSounds like I should read this someday. But first I have to read several other non-mystery books that I have purchased based on your posts (or the guest blogger's posts).

ReplyDeleteOne day, Tracy. It is really good - and you might be able to get a free or cheap e-version.

DeleteI've only just caught up with this, but I agree to the last syllable. 'The Go Between' was one of the first 'grown-up novels' I ever read and I remember thinking, aged about 13, 'but he knows EXACTLY how children think!' It's a couple of decades now since I last read it, but I feel as if I turned the last page yesterday. That description of clothes is seared to my memory, as is Leo's attempt at grown-up humour: 'I'm a chilly sort of mortal' which leads, humiliatingly, to laughter at his expense. Everything fits together with beautiful precision: the weather, Leo's belief in personal magic, the glorious perfection of the day of the cricket match and the terrible fall thereafter. You're right - it's perfect.

DeleteYes yes yes exactly. I am kind of furious that no-one MADE me read this book years ago - it's the kind of book that should be on top 10 lists, and passed on as one of those titles you know your friends will love. But my impression, certainly, was 'old-time white male whinging and repression', and no-one put me right. (You are let off because I haven't know you long enough that you should have told me.)

DeleteNumber 29 on this: https://storify.com/LissaKEvans/books-i-like

ReplyDeleteOk - you did try! And I have the fun of reading through the rest of your list, some of which I saw on twitter.

Delete